WELCOME TO THE BURGH BLOG

The Maryhill Burgh Halls blog offers a rich tapestry of stories, research, and reflections that celebrate the history, heritage, and community spirit of Maryhill, Glasgow. It features contributions from local historians, volunteers, and staff.

Scroll down to read and email info@mbht.org.uk if you would like to share something of your own.

Remembering Maria Fyfe

Words by Anabel Marsh

Maria Fyfe (née O'Neill; 25 November 1938 – 3 December 2020) served as Member of Parliament for Glasgow Maryhill from 1987 to 2001.

When I arrived at the Maryhill Burgh Halls as a volunteer in 2015, I had several years as a Glasgow Women’s Library tour guide behind me, and I was asked if I could create some similar women’s history material for Maryhill. When it came to choosing political women to include, I went for three spanning the twentieth century: Suffragette Jessie Stephen, Jamesina Anderson who was a councillor mid-century from 1945-1962 and, of course, Maria Fyfe. When I realised that she had been born in the Gorbals I also made sure she was included in the Women’s Library tour of that area. Her passion for equality making her a perfect fit.

Maria was elected as Maryhill’s first female MP in 1987 and served until 2001. A Labour Whip once revealed that in their office they sang songs about certain members. In her case it was ‘How Do You Solve A Problem Like Maria?’, but rather than take offence she chose this as the title of her memoir, subtitled A Woman's Eye View of Life as an MP, which covered her fourteen years in Westminster in what was then, and still is, a male-dominated environment. Two examples illustrate this.

First, as the only female Scottish Labour candidate in 1987, Maria wasn't surprised to be asked for a press interview. When the journalist said he wanted to write a contrast piece about her and the Tory MP Anna McCurley she asked him what issues he had in mind. She was left speechless when he replied, "Oh nothing heavy like that, it's just that you're a brunette and she's a blonde."

Second, Maria had a successful front-bench career, but said: “I am proudest of having been involved in the 50-50 campaign to ensure that the Scottish Parliament started life with an almost equal representation of women". She recalls the Chair of the Scottish group of Labour MPs at the time reacting to her statement that such equal representation should be the case. “His jaw literally dropped. He said, ‘You cannot be serious’ ”.

How have things changed? Not enough! There are fewer women MSPs now than there were in 1999 (although, as Maria pointed out, in the 2019 election to the UK parliament, Labour elected 104 women MPs out of 203). Female politicians are still subject to misogynistic objectification and abuse, but without women like Maria blazing a trail, things would be worse. As she said in a further volume of memoirs, Singing in the Street: We cannot wallow in misery. We have to fight.

“We can all try to have a little of Mary Barbour in us” - Maria Fyfe

When Maria died in December 2020, that fighting spirit drew cross-party praise with First Minister Nicola Sturgeon calling her a "feminist icon" who had been a personal inspiration to her as a budding politician. It was a spirit which had remained alive even after retirement from elected politics. For example, Maria was instrumental in the campaign to raise money for the statue of Mary Barbour, which was unveiled in Govan in 2018.

A few years ago, I attended an event to consider the short-list of designs for the Barbour statue, and made the mistake of telling Maria that I’d put her in two women’s history walks. Her look said that she definitely did not like being considered part of history! Now, sadly, she is. As Maria said of Mary Barbour: ‘’ Look how much she and her army achieved in the rent strikes of the First World War, and they didn’t even have the vote.’’ When people remarked, “If only we had a Mary Barbour today” Maria would always respond, “We can all try to have a little of Mary Barbour in us”. Maria was one who succeeded – and maybe we should all try to have a little of Maria Fyfe in us.

Maryhill: Tales of Temperance

Words by Ruairi Hawthorne

About twenty minutes from where I live, in the churchyard of the New Kilpatrick Parish Church in Bearsden, lies a very unique obelisk. It depicts a bridle hanging from a nail, a symbol of restraint and self-control. It is a commemoration of a man named James Stirling who, in 1832, made a pledge with seven other men to abstain from the consumption of alcohol and spirits for the rest of their lives. This would lead to the formation of the British Association for the Promotion of Temperance in 1835, and in good time many more working-class men made the same pledge.

You see, by James Stirling’s death in 1855, such commemorations where reserved only for those of high stature or renown, which is a real testament to the impact that James and his fellow founders of the BAPT made on the lives of many working-class drinkers, inspiring them to pledge abstinence and better their lives. This is best exemplified by the epitaph on James’s tomb, which reads: "He brought happiness to many homes where unbridled drunkenness has caused despair'. It can’t be denied that drink and drunkenness was ingrained into the lives of working men and led to much hardship, but why was this the case? Also, why was this plague of "unbridled drunkenness" so frowned upon by society’s upper echelons, despite drinking itself being so prominent in all social spheres? Finally, how did organisations like the BAPT try to combat it?

First Breaths

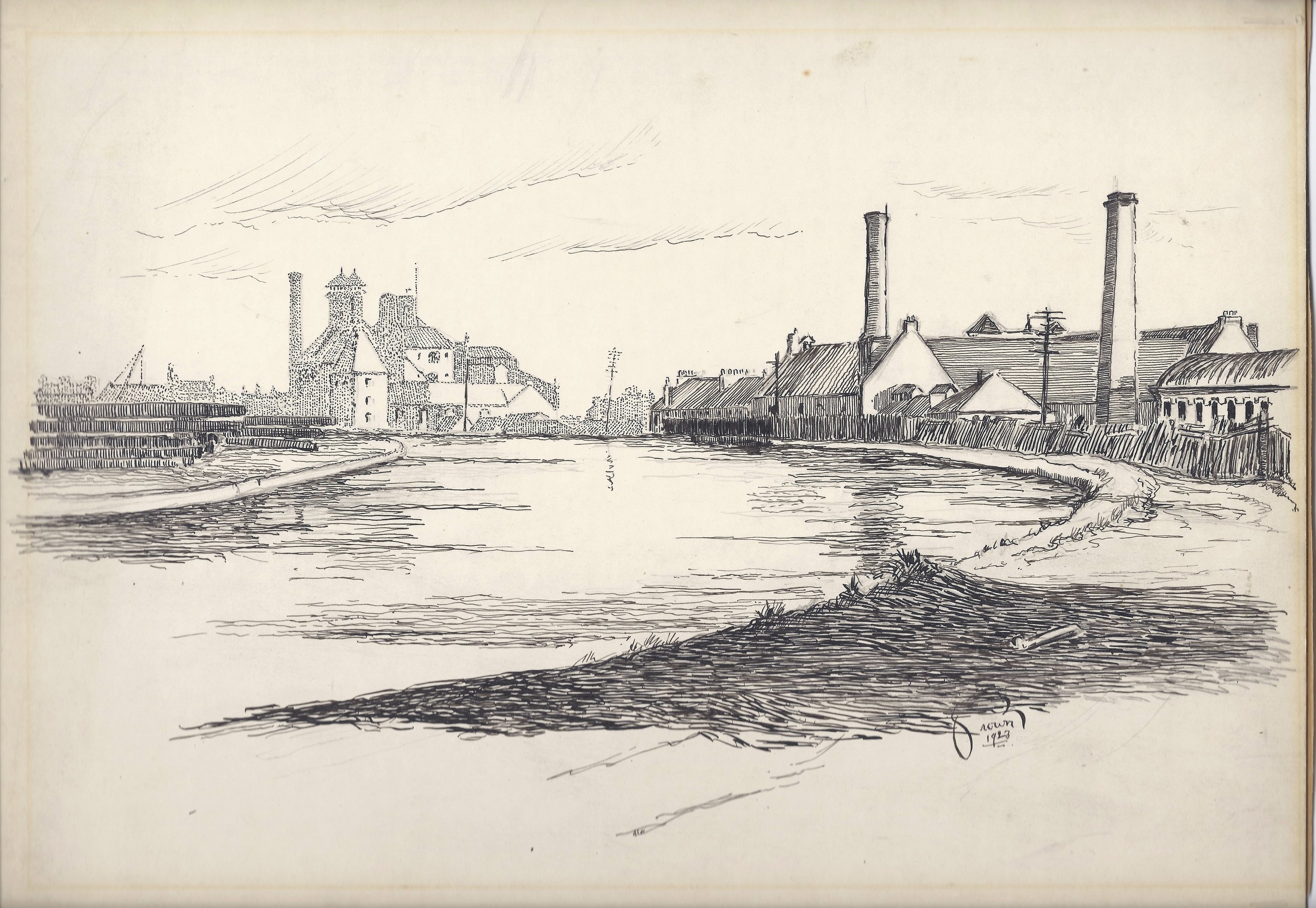

John Dunlop’s Portrait

The first breaths of the temperance movement in Scotland came on October 5th, 1829, with the formation of the Glasgow and West of Scotland Temperance Society. It was created by John Dunlop, who is now seen as the father of the temperance movement in Britain. He was a landowner and family man who had witnessed the decay and destitution that alcohol dependence had brought on men and their families. Shortly after John Married, his father, who was a wealthy banker, went bankrupt, threatening John’s inheritance and his family. John spent this time when his future was uncertain in prayer and contemplation, thinking about what he would do to cure society’s woes if he had the resources. Fortunately, this matter was quickly resolved thanks to a legacy bailout and soon his inheritance was secured. After being faced with losing everything, John endeavoured to use his inheritance for the betterment of others by combating what he saw as the greatest threat to industry, family life and finance: alcohol abuse.

At the first gathering of his new sobriety society in Greenock, he declared that he would forever abstain from partaking in spirits and stated his belief that poor education was one of the main contributors to the “demons drink” having such a strong hold on Scotland’s workers. That night, four other men made the same promise after hearing Dunlop speak. Sound familiar? This was known as the pledge, and it laid the foundation for a concept that is still found in modern AA and temperance groups to this day. While this many pledges may seem like a paltry number, it was more than enough for Dunlop, and the success he found with saving these four souls was all the inspiration he needed to continue his dry crusade. Where did he take his sobriety sermons next? Why Maryhill of course.

Moderation in Maryhill

In 1829, Maryhill was still a plucky little burgh that had yet to become part of Glasgow. It quickly earned the moniker “Venice of the North”, which was in reference to its dependence on its vast canals to accommodate it's production of vital resources. While this proved to be prosperous for the once humble burgh and provided many men with steady employment, the work was far from comfortable, and many of Maryhill’s men turned to liquid courage to kill the pain of their labour and forget the day’s hardship. At this point Maryhill had 23 pubs, which meant that there was one pub for every 57 residents, more than enough to drown one’s sorrows. It couldn’t have been more appropriate that this was where Dunlop turned his gaze next. Maryhill became the sight of one of the first British temperance societies, created as a combined effort between himself and his aunt Lilias Graham, who was a significant temperance crusader in her own right. John and Lilias took the Maryhill movement very seriously and may have considered this to be a familial duty, as they could both easily trace their heritage to the burgh’s creation. You see, Lilias was formerly known as Lilias Hill, daughter of Mary Hill herself!

In his ongoing quest to promote his spite towards spirits, Dunlop was filling the various venues of his grandmother's home with its many labourers, who had fallen victim to the demons drink to some extent. However, no matter how many of Maryhills children took the pledge at the end of the night, Dunlop's message of moderation and moral resilience was severely limited by two main factors. The first was that he was only one man, and he could not keep track of his pledges after he had finished his lecture. These men could try there hardest to live by his words but there was no one to go to for guidance if they found themselves tempted back to the simple comfort of alcohol. Secondly, even if every single man that swore to moderate their intake was able to stand by their pledge, Dunlop could only take his message so far due to the inherent limitations of transport at the time.

Allies

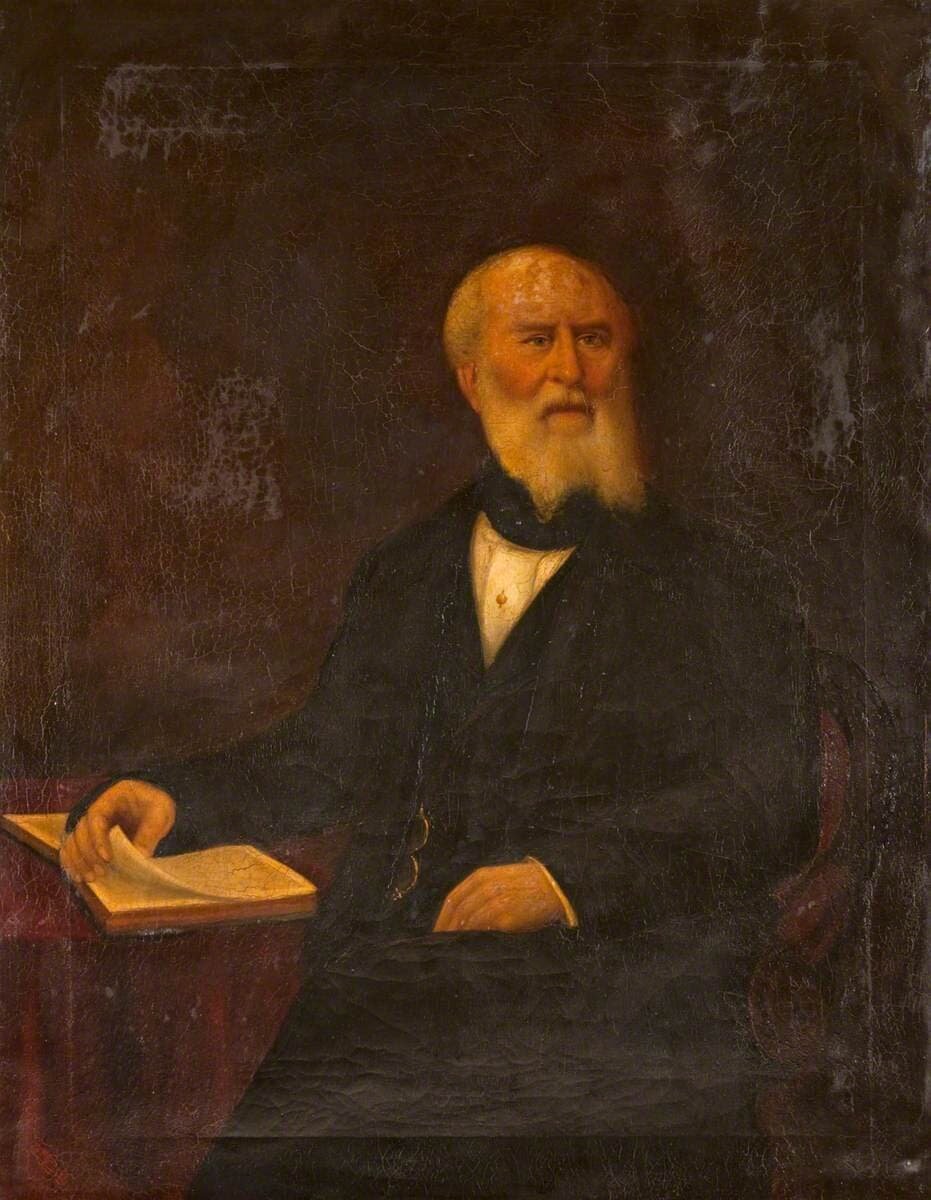

William Collins’ Portrait

Both of these placed severe restrictions on the scope and duration of Dunlop's influence, reguardles of how rousing his speeches where. In another striking parallel with his Grandmother's tale, the solution to John's two greatest obstacles would arrive without his influence or control. The first was in the form of an ally: William Collins, a publisher whose company is now known as Harper Collins. Despite the magnitude of his publishing house now, he began his working life working in a mill, and quickly noticed the often-drunken state of many of its employees, including the women. He found the frequent inebriation of the mill girls to be particularly disturbing, which eventually caused him to leave the mill and use his experience there to open a publishing house, which was simply named "William Collins Sons". However, Collins was not content to use his newly established company as merely a means of lining his pockets and climbing the economic ladder. Like his future colleague Dunlop, he was a first-hand witness to the destructive influence of drink on workers and wanted to use his newfound wealth to make a difference.

However, there was a key difference between the two: Williams, possibly due to having a more first-hand account of the societal woes wrought by alcohol, believed in absolute abstinence. He believed that most of the less fortunate members of society could not be trusted to simply moderate their alcohol intake, and that if they wanted to exercise control of their physical and mental well-being, they would have to quit all together. While this fundamental difference in approach would cause conflict between the two, they had a mutual respect and recognised that they both needed each other. Collins needed Dunlop to spark interest in the Temperance movement were ever they went with his way for words and passionate speeches, while Dunlop needed Collins to reinforce his message with pamphlets, posters and books. However, the second problem that limited to spread of the duo's message still persisted, transport. However, this would soon change with the advent of Britain's new, vast network of railway tracks. This innovation would assist Dunlop and Collins in carrying their message all over Britain. The relationship would eventually collapse under the weight of the pairs fundamentally different approach to temperance, with Collins being drawn to the allure of the growing prohibition movement, and Dunlop left to overcome being ostracised by the wider temperance movement on his own.

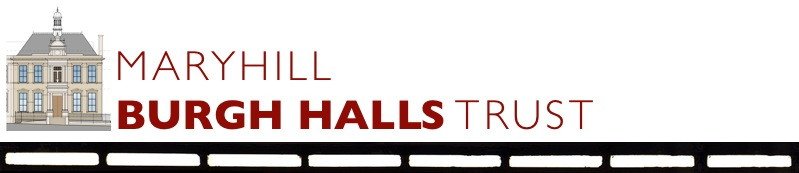

Kelvin Aqueduct, Maryhill.

As I mentioned before, Dunlop was convinced that there was more than drink to blame for the woes of the working class, namely, poor education and working conditions, as well as the drinking culture that had rapidly normalised public drunkenness. The former ensured that those who could not pay for a private education where almost certain to pursue unskilled labour as they weren't equipped to work in any other field. The latter ensured that the aforementioned unskilled labour would be mentally and physically painful enough to drive most men to the blissful warmth of liquor. However, among both allies and among those who made the pledge, Dunlop's calls for social reform often fell on deaf ears, with his colleagues often claiming that self-control was the only obstacle on the path to sobriety and his pledges seeing widespread improvement of education and workers’ rights as a pipe dream.

This wasn't helped by the fact that most British politicians would back the brewers and pubs when there was any talk of the country's problem with drink, with many seeing the temperance movement as a fad that would soon outstay it's welcome. However, the demand for social reform forced them to acknowledge the issue, although the only major legislative changes related to the subject was the mandatory price raising of alcohol, which only made the stuff more financially damaging to the less fortunate. In fact, John's brother, Alexander Dunlop was a prominent politician. He was one of the few who brought the issues of social and economic injustice up in parliament and was always trying to convince his brother to get into politics. However, John preferred to remain a civilian and he began working full time for the Temperance cause, losing most of his fortune in the process.He moved to London in 1836 and continued to dedicate himself to the movement until his death in 1868.

While his death may seem like a tragic one, he was survived by his wife, Janet, and his nine children. He was also father to an idea, that society could change for the better and that its less fortunate members didn't have to remain victims to the many destructive forces that had claimed the lives of so many. People like James Stirling continued to take the pledge, not just to abstain from alcohol but to strive towards a more kind and just society. I think now more than ever, Dunlop's dream is something that needs to become a reality.

Stirlings Grave. Photo Credit: Ruairi Hawthorne

The Roxy: A Tale of two Cinemas.

Maryhill Roxy

Words by Ruairi Hawthrone

Hello again, readers. While I took great pleasure in illuminating the excess and eccentricity of Mr Pickard last time, (a subject I may return to soon) for this article I have decided to return to one of my favourite subjects, the world of Cinema.

The subject of this piece, The Roxy Cinema, has quite a different story than my last subject, the Seamore Picture house, although both had the same objective: to capture the glitz and glamour of Hollywood and bring the wonder of the silver screen to the masses. This is best exemplified by its name, which was originally “The Picture House” which while functional, didn’t really bring that abstract pizzazz that would be needed to stand out from the rather crowded space of Glasgow cinema.

The Big Apple

The NY Roxy, Source: WikiCommons

If they were looking for pizzazz, they looked in the right place for inspiration: New York. The “Roxy theatre” opened in 1927 just outside off “Times Square”. It made its dazzling debut with a showing of Albert Parkers silent drama “The Love of Sunya”, and continued to enjoy great success as host of both motion pictures and stage shows until its closure in 1960, just before the advent of widely available colour television.

The titular Samuel L Rothafel, aka “Roxy”, was the basis for the theatres title. He was a theatre operator who was given a handsome salary and other benefits to bestow the theatre with its memorable moniker, as well as oversee its construction and operation. While it was named after Roxy it was the brainchild of Herbert Lubin, who intended it to be the first of six “Roxys” in the big apple, however things got off to a rather precarious start. From the beginning, Roxy wanted the theatre to be his greatest contribution to the world of the arts and spared no expense on its construction, hiring the architect Walter W. Ahlschlager and decorator Harold Rambusch to help with the buildings design. Ahlschlager was able to make good use of the limited space that they had to build on, prioritising seating capacity over everything else. This and many other last-minute decisions turned an already expensive venture into an astronomically over budget one. Unfortunately, this pushed Lubin into near bankruptcy, forcing him to sell his shares of the theatre to William Fox. This turn of events would shatter Lubins dream of owning a top of the line cinema chain, but this wasn't the end for the Roxy.

Roxy NY Weekly Review, Source WikiCommons

Despite the misfortune of the dreamer Lubin, the Roxy Midway Theatre (the only one of the planned six Roxy's to be built) flourished as a top class establishment. While Roxy's spare no expense mentality ended up being unfortunate for Lubin, it did pay off for its new owner, as it's luxurious facilities and extravagant design captivated visitors and allured staff. These facilities included a cafeteria, nap room, library, billiards room, gymnasium and showers to accommodate its staff. Meanwhile the performers enjoyed two stories of private dressing rooms, three floors of chorus dressing rooms, a rehearsal room, and a costume department. The staff did not have it easy however, as to keep up the standards of excellent manners and efficiency, the male ushers where subject to daily inspection's and drills by a retired marine officer. This combined with incredibly sharp film image and the inclusion of a 110 member symphony orchestra for certain showings enabled the Roxy to be the best of the best, just as its creator had envisioned.

However, the misfortune did not end with Lubin. Despite its many successes, the Fox Film Corporation, which was owned by the man who currently had majority ownership of the Roxy – William Fox – was in major financial trouble due to the advent of the great depression. This led to a number of crippling issues for the Roxy, including the fact that they could no longer afford to play A class movies, which was one of the major draws of the theatre. These issues where compounded by (and probably the reason for) the departure of the titular Roxy who left to pursue his own ventures and took most of the staff with him. Things where never quite the same without Roxy and while his successor, A.J Balaban, was able to keep the theatre afloat for another ten years by substituting high quality films with stage performer's, it never returned to its glory days.

As it turns out though, theatre runs in the family, as after Balabans departure he was replaced by Roxys true successor, his son Robert C. Rothafel. Unfortunately, despite the best efforts of both Blaban and Robert to once again turn the Roxy into a place of innovation and luxury as well as their genuine belief that "the theatre should be a veritable fairyland of novelty, comfort, beauty and convenience", the Roxy Theatre closed its doors the 29th of March 1960. Its final film showing was of the Ralph Thomas film “The Wind Cannot Read”, its use of sound and colour being the perfect illustrator of how far the Roxy (as well as film in general) had come since the theatres opening in 1927. It is still revered today for the philosophy’s of its various owners and its innovative use of music, live performers, and film. However, the story of Maryhill’s own Roxy is a very different tale.

Maryhill’s own Roxy

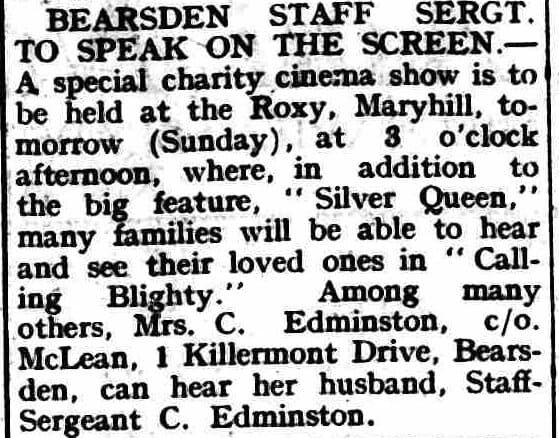

Maryhill Roxy Newspaper Clipping from the 12th of May 1945, at the end of WW2. Families could see loved one who were abroad at the theatre. Source British Newspaper Archive

Maryhill Roxy AD from February 1935, The Milngavie and Bearsden Herald. Source: British Newspaper Archive

Opened in 1932, Mayhills Roxy was a far cry from its American cousin, it based its name on the New York establishment’s and proved to be extremely popular – to this day holding a special place in the hearts of many Maryhill Denizens. Thanks to the efforts of architects Daniel Lennox and David McMath, the Roxy had a respectable 2,000 seats, a good percentage of them being occupied by soldiers from the nearby Maryhill Barracks. Not unlike its predecessor, the people in charge new that one of its main priorities should be bringing a wide variety of entertainment to the masses and making that entertainment much more affordable than the competition. To that end, they would host talent contests alongside their normal selection of films, broadening the scope of their audience considerably by creating an inclusive and welcoming environment. Many regulars have fond memories of going on dates, sneaking in through the women’s toilets, going to the nearby café (famous for its “so thick you can stand your spoon up in it” soup) and of course, being utterly absorbed in the world of cinema. One patron recalls being so enthralled by the exploits of Doctor Who that he let his ice cream melt down his trousers, while another recalls there envy of a frequent visitor who had a lengthy winning streak in the weekly signing contests. Even people who are too young to have visited The Roxy in its heyday have been regaled tales of heroic ushers and villainous visitors by parents and grandparents. Despite the many fond memories that the Roxy bore, it was closed and demolished in 1962, possibly for similar reasons to its New York counterpart.

The ever changing face of cinema

In the end, it seems that no picture house, regardless of size, staff or overall quality, is immune to the entropic force of colour television. While this innovation did not kill cinema by any means, it did spell the closure of swaths of picture houses worldwide, resulting in a landscape where only the strongest would survive. Now it's very difficult for small theatres like the Maryhill Roxy to survive and to attempt a venture as costly as the New York Roxy would be suicidal. Even the giants of the industry have resorted to a multitude of gimmicks to incentivise leaving the house and to justify ever inflating ticket prices, not unlike the NY Roxy in its later years.

These have included 3D (both in the 70s and its brief revival in the 2010s) 4D, D-Box Seats, increasingly sophisticated surround sound systems and strangest of all, the short-lived Smell-o-vision. These may seem like the last gasps of a dying industry, however the major chains like Cineworld and even independent theatres such as the GFT have continued to remain profitable, especially when they abandon short sighted gimmicks and focus on there respective strengths, the former bringing major releases to the masses in massive, comfortable screens and the latter bringing the obscure, low budget and foreign pictures to people who would otherwise be unable to see them. I see the aforementioned theatres as the modern successors of the two Roxy's, and I hope that they can continue to embody the bombastic, adventures spirit of Samuel and the subdued charm and underdog spirit of the beloved Maryhill Cinema for years to come.

My time volunteering at Maryhill Museum

Words by Jess McManness

I’d like to share with you some thoughts and reflections on my time spent volunteering in collections management at Maryhill Burgh Halls. A bit of background for you—I’m a current postgrad student (soon to be graduate) at University of Glasgow in the field of Museum Studies. As a part of our course load, each student selected a work placement with the goal of gaining practical, hands-on museum experience, and I already had an idea of where I wanted to go. MBHT’s heritage manager, Nicola McHendry, had spoken on a panel for one of my first classes at UofG. Through this dialogue, I came to know Maryhill as a small, but feisty museum with a strong voice and a deep commitment to its community. I wanted to work in an environment that had those close community ties. My placement choice was clear, and I went into Maryhill Museum collections management with another student volunteer, Rachel, who became my project partner and a wonderful friend.

Rachel (left) and Jess (right) in Kelvingrove Park

My first day volunteering for Maryhill Museum was a bit nerve-wracking, but almost immediately I came to understand that Maryhill is a family—one that is warm, welcoming, a bit rowdy, and intensely supportive. Days working for Maryhill Museum were filled with explorations of collection storage, diving through stories of the past, sharing discoveries with others in the office, laughing at the antics of the other volunteers, and frequent trips downstairs to the café for heaping cups of hot mint tea.

Rachel and I’s foremost job was the cataloguing of the Maryhill Museum collections. The end product of this was a collections database populated by artefact profiles. Each profile includes photographs, biographical info, and research pertaining to individual artefacts from the museum collection. My favorite discoveries in the Maryhill Museum collections gave the past new voice and color. Transcribing the backs of postcards offered insight to the everyday stories the past is built on.

Many messages were quick life updates such as the 1906 postcard, Girl’s Industrial School, Maryhill (2010.11) which reads: “Dear Cousin Helen, Mother still pretty weak, not out yet. We got back all right, for which thank you very much. The frocks are very nice. Baby has been ill and the Dr is still coming to see him. I will write a letter soon. Hope you are well.” What has both mother and child ill? What were common diseases of 1906? How much would a home visit from the doctor set you back? The questions raised through an examination of this postcard present avenues of inquiry into local Maryhill life, as well as an opportunity to hear the voice of a local Maryhill woman.

The collections at MBH are held in trust for the Maryhill community. Always remember that they belong to you. One of the most exciting parts of this project is that the beginning of our collections database is now accessible to the Maryhill community, local and extended. You can explore the Maryhill Museum collections for yourself here. There is so much more left to be done within our collections and so many stories yet to be told. Hundreds of artefacts are still shelved in storage, waiting to enter the system.

Research on a Maryhill railway ticket in its wider context

As a museum volunteer, there is always more work to be done. Working at a small, largely volunteer-driven museum, you have a lot of opportunity to expand yourself into other areas of interest, because there’s always a need for more helping hands and ideas. MBH volunteers really run the gamut of day to day tasks and fill many roles, including collections care, research, tours, talks, fundraising, and social media. Though I was working primarily as a collections manager, I also had the opportunity to curate a display case for the entrance hall, hang exhibits, and attend the annual board of trustees meeting. Little opportunities would pop up all the time and really allowed Rachel and I to grow and expand our skill set. As both of us look to take further steps into the heritage sector, volunteering at MBH provided us with necessary skills and experience which have already proven invaluable.

“I came to know Maryhill as a small, but feisty museum with a strong voice and a deep commitment to its community. ”

Jess hanging an exhibit in the Halls.

Though I must now end my time at Maryhill, its vibrancy, stories, and people continue to be in my thoughts. And that’s what a museum should do, isn’t it? It should stay with you, even as you leave.

Thank you, Maryhill Museum!

If you would like to get involved with Maryhill Museum please email heritage@mbht.org.uk

Maryhill Barracks

Words by Scott Hope

Our Flag, Our History – Maryhill Barracks

The Maryhill Barracks opened in the 1870s to replace Glasgow’s aging Infantry Barracks at Duke Street in the east end – although at the time, Maryhill wasn’t even a part of Glasgow yet!

The building of the barracks brought our burgh and the city ever closer together. The new presence of soldiers gave Maryhill a garrison town feeling. You’d have seen soldiers in their trews and kilts on Maryhill road and you’d have heard marching drills and training over the walls of the barracks. And in 1918 you’d have seen soldiers leave the barracks, destined for France and the trenches.

Maryhill Barracks Gate

The barracks are an important part of Maryhill’s history and might even feature on your flag design…

Some design elements to consider:

Elephant and Bugle (The Emblem of the HLI, a regiment based at the barracks. The Lockhouse pub used to be called the Elephant and Bugle and there was another pub simply called the HLI, whose decorative solider sign can be seen in the burgh halls to this day)

Wynford Housing Estate (After the Barracks were decommissioned, in the 1960s they became a new High Rise living complex, The Wynford has a tremendous sense of community and the building form an Iconic part of the Maryhill skyline)

The Barracks Wall (Despite the sites redevelopment in the 60’s, the original perimeter wall remains, creating a striking distinction between the modern architecture and Victorian barracks wall)

A.E Pickard and the Britannia Panopticon

Words By Ruairi Hawthorne

Hello again! Sorry it's been so long since my last article. I hope you enjoyed it and that it could take your mind away from these trying times, even if only for a moment. You may remember that the man who owned the subject of my last article, The Seamore Picture House, was a man named A.E Pickard. During my research on that topic I was fascinated by the small glimpses that I got of this man's life, concluding that he could easily be worth dedicating more time of the article to. However, I realised that this would probably draw focus away from the main subject – so here I am, ready once again to delve into Glasgow’s past.

A.E Pickard was born in 1874 in Bradford. Despite his English heritage we can consider him a true Glaswegian as this is where he spent most of his life, moving here in 1904 and dying here in 1964. He arrived in Glasgow and pursued the only career that could accommodate his future of excess and eccentricity – show business!

Albert Ernest Pickard

By the time he arrived in Glasgow, Pickard was already well seasoned in the world of work, he was only ten when he began his training as an engineer. Besides this, little is known about his childhood and early adulthood, although based on small scraps of information it appears that he dabbled in every conceivable industry. He gave up his most recent prospect (a printing apprenticeship) for his new ambition of becoming a traveling showman, plying his new trade in the bustling cities of France, London and Yorkshire. When this proved to be unfruitful, he pursued his new ambition owning property in Glasgow and within three months of moving here he had made his first purchase.

The Britannia Panopticon

The Britannia Panopticon (originally the Britannia Music Hall) was opened in the centre of Glasgow, sometime in the late 1850s and had the daunting task of entertaining thousands of local workers seeking some escapism. Since the 1500s the main source of this entertainment for working class Glaswegians was–rather grimly–public executions, a hard act to follow for the Panopticon. This mob mentality among the patronage meant that any performance failing to satisfy would be met with through projectile abuse in the form of rivets, turnips and horse manure.

The place quickly developed a bad reputation but after several changes in management it ended up in the hands of James Anderson. The previous owners, husband and wife team Mr and Mrs Rosenberg, had done a great job in giving the place a new life by introducing many respected music acts as well as innovative features such as showings of animated films and performers who incorporated electricity into their sets. Despite these features making the Panopticon one of the most popular venues in the city, by the time Anderson came on the scene in 1905 the place seemed to be on its last legs and was considered a relic of the old century. This is where our protagonist, A.E Pickard, came in.

James Anderson's neighbour at the time happened to be none other than Mr Pickard. Anderson had seen his success with reopening the neighbouring "Fells Waxworks Museum", feeling that his knack for showmanship might be the Panopticons salvation. Pickard spent several months renovating the place, turning the attic into a carnival. This carnival was complete with the typical fortune telling machines, electric rifle ranges and hoopla’s as well as the rather atypical wax figures, which was an ever-changing exhibit as they depicted the most recent person to be executed at Duke Street Prison. That last example is a great insight into Pickard’s often macabre sense of humour which would end up being a major motivator of his later exploits. He later converted the basement into a "Noah's Ark" zoo, with reptiles, monkeys and even a bear! This basement also included distorting mirrors, paintings and medieval Chinese etchings of torture.

The Britannia with Pickard at the helm.

Pickards "throw everything at the wall" technique definitely payed off as it brought back the old working class crowds, who may have been alienated by the previous owners attempts to legitimise the place. This is evidenced by the fact that few of them could actually pronounce the word "Panopticon", leading it to be commonly known as "The pots and pans". Pickard had a very hands on approach to running "The Panopticon", dishing out the same kind of mob justice that the performers had been subjected to 50 years ago, although this time the nails where being thrown by Pickard, usually from a stage ladder, at the audience if they ever got out of hand. The performers where not immune to this treatment however, as Pickard would often try to use a long pole with a hook at the end to pull them of the stage if he thought that they weren't up to much.

Amongst the myriad of performers that set foot on this stage, from the tried and true bearded lady to the ever put upon world's smallest man, the one who left the most enduring mark on the world of performance was a sixteen year old boy named Stan Laurel…..

1941 | The Luftwaffe Bomb Kilmun Street, Maryhill

Kilmun Street Maryhill – Ian Fleming

Words By Scott Hope

To mark the 75th anniversary of VE-Day, here is the story of the Maryhill Blitz, when a part of Maryhill was levelled by the Luftwaffe. It’s an episode that has been passed down in my family, but you might not have heard of it.

Rescue Party, Kilmun Street – Ian Fleming

During the height of the Clydebank Blitz, the 14th of March 1941 was a roundly bad night for the west-end of Glasgow and Maryhill. First, Queen Margaret Drive was hit – 3 people died and 500 homes were damaged in the area.

Later that evening at midnight, the German Bombers struck again. This time, it was further north and further west; at St Mary’s School and Kilmun Street in Maryhill. It was a Friday night, the tenement flats which then stood on the street would have been all but full – my great grandparents included.

A pair of mines first exploded in a nearby field, the blast damaging St Mary’s which at the time was housing an AFS (Auxiliary Fire Service) post; as RM Scott, the air-raid warden explained. “Blast from the first mine wrecked the school known as St Mary's RC school. The wide front of red stone withstood the blast but windows were torn out, rooms wrecked and doors blown to atoms.”

Scott himself was actually blown on to Maryhill Road by the blast, only to come to surrounded by tea packets, one of a few bits of dark humour to come out of the scene: “The second blast caught me in Maryhill Road and it was a bit of a comedy to find one's self surrounded by Cochrane's tea packets and no ration books required”.

The second blast was in the back courts of the sandstone flats on Kilmun Street. Numbers 32 and 36 were destroyed as were houses in Shiskine Street, Kilmun Lane and Kirn Street, and several others being set on fire. As a resident, Ms McNeil, said in RM Scott’s report: “The sky was bright red, this was Kilmun Street burning–the warden said; 'Kilmun Street's away'. Well you can imagine how I felt going into the shelter.”

Civilian deaths register, Edinburgh Castle War Memorial

83 people died in the bombing on Kilmun street that night with a further 180 injured. My great-grandparents were among those who emerged to find their flat at number 36 gone. My great-gran was actually pregnant with my grandad at the time, who was later born in July 1941. Had they been less lucky I wouldn’t be sat here writing this today–the eerie thought of which usually hits me when I pass Kilmun street.

If you read RM Scott’s report on the incident – linked at the end of this piece – what you get is a real sense of community spirit: “someone came and told us to go to the tramway. There was an old man up the stair and when we were going in, my mother was so busy looking back to see if he was alright she actually fell into the pit. Luckily she wasn't injured.” –Ms McNeil, Scott’s Report.

However, some stories from the incident are imbued with a tinge of dark humour – or are even just blatantly macabre. Some are more anecdotal than others.

In one of the more anecdotal, somebody–somehow–slept through the bombing with the help of a drink or two: “a man who, having indulged generously in John Barleycorn on the previous night, went to sleep in the recess bed of his flat. He woke up feeling a cold draught and, shouting “Gaun’ tae shut that door Jessie” turned over, only to find himself facing a yawning gap. Half of the building had collapsed, leaving the bed and its occupant hanging precariously above the debris.” –Bill Black.

In one, sadly backed up by Scott’s official report, a young mother was found wandering around the street in the aftermath, clutching her headless child in her arms: “I don't think too much about the terrible sights -the woman clutching her baby with its head blown off and people being dug out all mixed up with dogs and cats and birds.” –Ms Rickard, RM Scott’s report.

One story that comes from my own family involves a bit of gallusness on the part of my great-grandad. Working in a reserved occupation – until being sent to Italy later in the war – he was paid his wages that Friday night and left them on the mantlepiece. In the aftermath, he slyly snuck into the rubble, managing to save not only his wages but also my great-gran’s wedding dress–although he was then rumbled and questioned when he was mistaken for a looter.

Over 100 homes were outright destroyed, a further 250 made uninhabitable and 100 shops damaged. Some residents were sheltered at East Park School in the days that followed. After the bombing, my family moved into a place further along Kilmun Street where they stayed for the rest of the war–at first, the new flat had no roof and it’s said in the family that they could see the stars from it.

With those flats long gone, Kilmun Street now lies empty–but next time you pass it, spare a thought for what happened there and those who lost their lives, I always try to.

Kilmun Street today

…

RM Scott’s Report – https://www.blitzonclydeside.co.uk/CHttpHandler.ashx?id=23369&p=0

1911 – Heady Heights

Thistle started the new year exactly where they had left off, recording a 7-2 Scottish Cup victory, over St Bernard’s at Firhill. The timeless phrase “could this be our year” was probably discussed in many of the countless Hostelries in the Burgh – Maryhill was said to have had one pub for every 59 inhabitants!

The Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry was held in Glasgow in 1911. It was the third of 4 international exhibitions held in Glasgow during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The University's tower overlooking the site of the exhibition

The exhibition followed two previous exhibitions, The Glaswegian Exhibition (1888)and Glasgow International Exhibition (1901). It took place at Kelvingrove Park, and ran from 2 May to 4 November 1911 and recorded over 9.3 million visits. The fair was held close to the River Kelvin structured around the Stewart Memorial and included a Palace of History (based on the Falkland Palace, a Palace of industry, a Concert Hall and an Aviation Building. Entertainments included boat trips, an aerial railway and a Highland Village (from which a cairn marking the village remains).

Meanwhile, a short distance away Thistle were providing entertainment of another kind, in “the beautiful game”. The Jags replicated their form of the pre-Christmas period and finished the season unbeaten at Firhill. The reward was a heady 4th place in the league behind champions Rangers, Aberdeen and Falkirk, only Dundee had managed to match their number of home wins, Celtic trailed in behind us in fifth place – which still brings a smile. A rare Firhill defeat was handed to the Jags by that same Dundee Team in the next round of the Scottish Cup (0-3). “Ach well, there’s always next year”.

1910 – Maryhill or Partick Thistle?

Thistle had very quickly become part of the fabric of Maryhill, and that throws up the question “Why not Maryhill Thistle?”. There have been many theories put forward, most of them speculative, such as they wanted to maintain links with their roots; they didn’t want to alienate their supporters from the burgh of Partick; the board were Partick men. The real reason is simple – there was in existence a team in the burgh - Maryhill that is – called Maryhill Thistle! Things were past being parochial by that time anyway with both Burgh’s having been swallowed up by the expansion of the City of Glasgow.

On the field of play, a modest improvement had been made, with the Jags settling in nicely to their new surroundings and after the final game of the season they found themselves in 16th position in the League.

The May saw the conclusion of that season, with the Scottish Junior Cup final being held at Firhill. Unsurprisingly Thistle’s neighbours Ashfield FC ran out winners with a 3-0 victory over Kilwinning Rangers.

The new season kicked off on 20thst August 1910 and Thistle must have done something that summer. If you could bottle it, you’d be a millionaire. A spectacular run saw the team reach the end of the year undefeated at home. The only team to leave Maryhill with dignity intact was St Mirren. The crowds continued to grow, with several matches being played in front of audiences in excess of 10,000.This spectacular run saw Thistle competing at the right end of the league table, in touch with the leaders, Rangers. Success was partly due to the attacking duo Willie Gardner and Frank Branscombe, the latter being considered a legend to this day. He was one of the group of mavericks, known as Firhill wingers. His story isn’t without tragedy though, in December 1909 he had been involved in a collision with James Main of Hibernian. the player died of his injuries four days later.

“Main's life and career was cut short, however, when he suffered a ruptured bowel after being kicked in the stomach by Partick Thistleoutside-left Frank Branscombe during a match played at Firhill on Christmas Day 1909. John Sharp, a teammate of Main, later said that the incident was an accident because the Thistle player had slipped on the icy surface before making contact.[1] Main had returned home on the night of the game, but he was rushed to Edinburgh Royal Infirmary when the extent of his internal injuries were realised.[2] An emergency operation was initially successful, but further treatment was ineffective and Main died from his injuries.” (source: Wikipedia).

Frank was deeply affected and so was his form, it was only at the beginning of the 1910-11 season that he truly established himself in the starting 11.

Frank Branscombe

A Maryhill Heroine Remembered | NHS Louisa Jordan

The naming of the Covid-19 hospital newly set up in the SECC in Glasgow may have raised an eyebrow or two amongst folk who had not previously heard of Louisa Jordan. Residents of Maryhill may not have heard of her either but her place in the history of Maryhill should be remembered, especially during this time of pandemic.

The Scottish Health Secretary, Jeane Freeman stated that "She is a person who has perhaps up until now been better remembered in Serbia than in Scotland. This hospital is a fitting tribute to her service and her courage."

Nursing Sister Louisa Jordan

So who was Sister Louisa Jordan?

Louisa Jordan was born on the 24th July 1878 at 279 Gairbraid St. Maryhill. (Gairbraid St. was the former name for Maryhill Road between Garscube Road and the canal bridge.) She was the only daughter of Henry and Helen Jordan who lived at 30 Kelvinside Ave. Her father worked as a white lead and paint mixer. She had two brothers, David and Thomas.

After working as a mantle maker, Louisa went on to train as a nurse at Quarriers Home, a Bridge of Weir sanatorium, before moving to work in Shotts Fever Hospital. After qualifying she moved to work in Crumpshall Infirmary in Manchester a 1st Poor Law hospital. On her return to Scotland Louise worked in Edinburgh and Strathaven as a Queen’s Jubilee Nurse. She then was transferred to Buckhaven where she worked as a district nurse serving the Fife mining community.

Following the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Louisa enlisted with the Scottish Women’s Hospital for Foreign Service in the December of that year and joined the 1st Serbian Unit under the command of Dr. Eleanor Soltau.

They set sail from Southampton in mid December 1914. By the time they arrived in Salonika, Serbia had managed to turn their fortunes around and had won the first victory of the war by pushing back the Austrian/Hungarian forces.

On arrival at Salonika the unit were sent to Kraguievac a city 100 miles south of Belgrade. Although the fighting at that time was minimal there was still a massive amount of work to be done. Serbia was well short of medical facilities and their time was spent tending to the wounded.

Typhus, a cold weather disease spread by body lice which thrived in the overcrowded, dirty conditions which were rife in Kraguievac, broke out in February 1915. By the middle of the month a typhus ward was up and running and Louisa, who had some experience having worked in Shotts Fever Hospital, was put in charge.

Also working with typhus in the wards at Kraguievac was Dr Elizabeth Ross. She was not a member of the SWH and had travelled to Serbia alone when war broke out and had been assigned the typhus wards of a Military Hospital. Louisa and Elizabeth knew each other well and when Elizabeth became ill with typhus Louise volunteered to help nurse her but sadly Elizabeth died on February 14 1915.

“We really felt we had lost one of our own” wrote Louisa. Sadly, this would be one of last entries in her diary as a few days later she died of typhus, soon after Madge Fraser and Augusta Minshull also succumbed to the epidemic.

Detail image of part of the "Women of the Empire" memorial panels in York Minster.

Photograph © Michael Newbury, May 2016.

Loiusa Jordan died of typhus in Serbia on 6 March 1915, age 36. She is buried in Chela Kula Military Cemetery, and commemorated at Wilton Church Glasgow and on the Buckhaven War Memorial.

The people of Serbia have never forgotten the remarkable courage and self-sacrifice shown by these women and today at Kraguievac they are remembered each year with dedicated ceremony. It is therefore fitting that Sister Louisa Jordan is also remembered in her home city during these difficult times.

Maryhill and the Movies: 'See More at the Seamore!'

A Glasgow tram passes the Seamore

Words by Ruairi Hawthorne

As a fan of movies and their history I’ve decided to regale you with the unsung tales of Maryhill’s relationship with film – and I hope that after reading this post you are filled with a newfound curiosity for both cinema and this endlessly fascinating town.

There have been a number of cinemas in Maryhill over the years so I should probably start with the oldest and in a sense still up and running Seamore Neighbourhood Cinema, formerly known as the Seamore Picture House.

The Seamore Picture House opened in 1914 during films infancy. "A Trip to the Moon" had capped things off in 1902 and is now considered to be the first example of science fiction in cinema and is arguably the first true feature film. This was followed by other classics of the silent era such as the "The Great Train Robbery" – the original western, which was released the following year – and, in Thomas Edison’s foray into the still uncharted territory of film, 1910s "Frankenstein", which as well as being one of the first horror films is also the first of a horde of adaptations of Mary Shelley's classic novel.

A programme and view of the seamore.

Credit: Oldglasgow.com

The Seamore opened on Maryhill Road in December 1914 just as things in the world of cinema where beginning to ramp up and was described as "The Greatest Achievement in Popular Entertainment" on its opening night. It was designed by GA Boswell and RA Thomas for flamboyant businessman AE Pickard.

His eccentric nature was reflected in the buildings odd design as its ceiling was adorned with nude paintings and later a large, revolving windmill on the roof. If was advertised with the slogan "See more at the Seamore", and it lived up to its name; playing films to the adoring public from its opening to 1935 (when it was bought by a new owner), starting with a screening of the comedy "Mabel's Married Life", starring Mabel Normand and Charlie Chaplin.

Like all films shown at the Seamore the ticket came with a stipulation that the patrons remove their hats when they entered. Despite his eccentricities Pickard was also a man of tradition as even when film marched into the era of sound (many would call them talkies for years to come) he would insist that only the silent classics be played. Although, he made up for his shunning of the advancement of cinema by having his employees put on song and dance routines before screenings, truly a unique experience.

However, despite some resistance, the venue was bought by a new owner who was more than willing to purge the place of Pickard’s own brand of strangeness as he was soon providing audiences the once forbidden "talkies" and removed both the buildings signatures, the nude paintings and the windmill. Now more willing to embrace the future of the silver screen, in 1953 the cinema was the first in the Maryhill area to be modified for CinemaScope, a new type of lense that could shoot movies in wide-screen. By this time the appeal of movie theatres was dwindling as television was making its mark and CinemaScope was created so that places like the Seamore could draw people back in. While CinemaScope did help rejuvenate the world of cinema at large, it was only a temporary boon for the Seamore as it was closed in 1963 due to low attendance and was tragically destroyed in a fire in 1968.

However, this story does have a happy ending as the Seamore lives on through it's successor "The Seamore Neighborhood Cinema", managed by Ross Hunter and a passionate team of volunteers. It is situated in the Community Central Halls and screens films every Friday and Saturday, aiming to cater to people from all walks of life but especially ones who cannot afford to make regular visits to the bigger chains.

The new Seamore cinema is hosted just down the road at Community Central Halls Credit: CCH/Facebook

They wear the name "Seamore" with pride and they endeavour to keep the place as accessible as possible, making film a luxurious escape from reality that anyone can immerse themselves in. They have achieved this by implementing many family offers to keep things affordable and, most impressive of all, they have outreach programs. These involve bringing portable cinema equipment to those who have limited mobility in a space that they feel comfortable in, a truly innovative process that lives up to its predecessor legacy of innovation.

Partick Thistle Moves to Maryhill

1909 – Immigration to Maryhill

Partick Thistle had started what was to be a defining year with a 0-6 loss to Rangers. Ironically the match was a home game played, of all places, at Ibrox! The Jags were refugees whose “home“ matches were being played at the Govan ground. After that fateful day they completed the season playing all their matches away. Unsurprisingly they finished 18th in the First Division. Something had to change.

On the park significant signings were made, in June Alec Raisbeck, a Scotland International with two English League winners medals, arrived from Liverpool in somewhat of a coup. Further raids down south were made, with Parry (Liverpool), Callaghan (Man City) and Graham (Everton) all joining the Dark Blue and White. Different days indeed, players from these illustrious clubs today would cost millions.

In an ideal world, The Board of the homeless Partick Thistle would have found accommodation within the Burgh of Partick. However, the search for suitable land there proved fruitless. It was therefore to the north they had to migrate and the neighbouring Burgh of Maryhill. How would the incomers be received by the hardened locals? After all football was very much a community pastime, unlike today where fans of the game travel across continents to follow their team. They needn’t have worried as the people took them to their hearts.

Firhill was to be their new home, nestling adjacent to a timber basin on the banks of the Nolly. On 18th September 1909, the first match was played on what is a personal “field of dreams” against Dumbarton Harp. A crowd of 5,000 graced the occasion and Thistle won 3-1. “Fortress Firhill” was born. I wonder whether my Great Grandfather, who lived on Springbank Street was there that day.

The teams form improved following the establishment of their tenancy in Maryhill and while being unspectacular, the people of Maryhill continued to turn out in healthy numbers to watch them. A crowd of 6,000 watched as the Jags hosted their first league fixture at their new home, the next home match versus Falkirk drew 9,000 and around 25,000 packed in to see them take on Rangers in a 0-0 draw. Progress was being made in all departments.

Thistle, as they were known to Maryhill citizens - we still get shirty today when outsiders and the uninformed refer to us merely as Partick, despite this progress finished rock bottom, 18th in a league of 18. It’s interesting to note that of the 18 teams which contested the First Division Championship that year, only two have been lost to the professional game in Scotland. Third Lanark and Port Glasgow Athletic are no longer with us.

Money was tight in those days, some things don’t change, but Firhill had been invested in, to the tune of £3,000, although the ground was rented. Thistle were here and here to stay!

Attention | MBHT Office/Reception Closed | Covid-19

Due to the coronavirus, Covid-19 outbreak, we have taken the difficult decision that from today our operations will be reduced and carried out from home.

We have made the decision as the health and safety of our volunteers and staff is key.

What this means in practise is that reception will be unmanned, the MBHT office and part of the museum/exhibition are closed. Our staff are still contactable, but working from home.

The 60's photography exhibition, 'The Way We Were' by Morton Gillespie is sadly partially closed. Some is still available to view in the main foyer – when we are back to normal service the exhibition will be properly opened, extended and celebrated.

The cafe at the moment will remain open. Security will still be on site and our tenants all still have access to the building.

If you have any queries please get in touch via info@mbht.org.uk

As ever, be safe and best wishes,

The MBHT team

Opening Postponed | The Way We Were

Dear all,

Sadly, due to issues with materials we have had to move our opening of Morton Gillespie's The Way We Were photography exhibition from today to slightly later in the week.

As it stands, we will have the exhibition open and available to view in the Halls from Wednesday the 18th of March (18.03.20).

We have also taken the difficult decision to – for the foreseeable future – postpone our launch event this Friday due to the current COVID-19 outbreak. The health of our visitors is paramount and as such we will reschedule the event when the public health situation becomes more favourable.

Please keep your eyes peeled for any further communications regarding the Halls activity – we will post updates here, on twitter and on our website.

Best wishes and be safe,

The MBHT team

Treasurer Wanted

We have this week, as part of Volunteers Week, had focus on our amazing volunteers who help run the Halls in different capacities. Right now we are looking for a very specific type of volunteer to join the board of Trustees . Read more here on the role and what it entails, and send us your CV if you are interested!

About us

Maryhill Burgh Halls Trust is a community-led organisation, responsible for the running of the historic Burgh Halls in the heart of Maryhill. The Trust (MBHT) was established in 2004 to bring the Halls back into use, and since the 2012 re-opening we have yet again become established in the Maryhill community. Besides activities we put on, often exploring the history and heritage of Maryhill, the Halls also include a café, a nursery, several office spaces with a variety of tenants, and venue spaces that are regularly used for rehearsals, conferences, and more. Through the Trust’s activities, there has been a resurgence of interest in Maryhill’s cultural, social and industrial heritage.

The Trust is a company limited by guarantee and a registered charity. It is managed and led by a voluntary community-based board of directors and currently employs two members of staff. We are currently looking for a volunteer treasurer for our Board of Trustees, who guide the future of Maryhill Burgh Halls.

The role

The Treasurer acts as Chair of the Finance sub-committee and holds several responsibilities:

Ensuring that financial procedures are adhered to

Overseeing financial reporting and advise on appropriate presentation

Overseeing (and where necessary, produce) budgets

Advising on and leading any review of financial procedures

Liaising with professional advisors, the bookkeeper, and relevant staff

Ensuring the audit is undertaken, accounts are prepared at the appropriate time and lodged with OSCR at the required time

Hours for the role are variable, at about 12 hours a quarter. Besides this, there will also be time spent going to and preparing for meetings, of which there are eight per year.

If you are interested in volunteering with Maryhill Burgh Halls, and have some experience in the finance and business sector or an accountancy background, please send your CV either by email to info@mbht.org.uk or by post to:

Maryhill Burgh Halls Trust

10-24 Gairbraid Avenue

Glasgow, G20 8YE

Building a Home for Heritage

On Wednesday the 23rd of May 2019 we invited members of the Maryhill community to come into the Halls for a chat about community heritage and the future of a Maryhill Museum. We have long been working on the idea of a Maryhill Museum, and are hoping to make this a reality soon (read more about our donation drive here). During our talk we learned more about what you think the museum should be like - free and accessible to all, a place that represents home and the rich Maryhill heritage.

As a community run charity with only two members of staff, the museum will, as it is now, be dependent on and shaped by volunteers. If you’ve ever entered the Halls and met one of our friendly receptionists, you know how volunteers make sure everything runs smoothly in the Halls.

But besides reception, there is also so much more you can help with! Even if it’s just for an odd hour here and there, reach out to heritage@mbht.org.uk if you want to get involved with the Museum and be part of an exciting community project. No matter where your hobbies lie, we can use them - and you get to be part of a fantastic, engaged team and flex your talents! For some inspiration, here’s a roundup of talents we would love to have on board.

We are also very open to people who want to take this as a learning opportunity to practice their skills. For those interested in collections care, historical research, and similar, we will provide training and ongoing support - making it a perfect opportunity for those wanting to get started in the heritage sector, or even those who are just interested in the history of the area.

Any questions can be send to heritage@mbht.org.uk or over our social media.

Preserving the Maryhill Museum

The Maryhill Burgh Halls Trust was established by local people in 2004 with the goal to establish and preserve the Maryhill Burgh Halls both as a historic building, and a centre for the community. Since our re-opening in 2012, the Halls have served as a space for small businesses, community events, and to display our local heritage.

The Halls have over the past 6 years put on many public events and exhibitions showing the local history of Maryhill, thereby building our heritage collection. But we need a dedicated museum space with space for our over 100 objects - Maryhill has a rich history, and we want to preserve and show it off! The collection includes paintings, medals, oral history, sound archives, poetry and photographs, and if we don’t have the appropriate space, these objects will need to be transferred somewhere else.

We want to make the history and culture of Maryhill accessible to local residents. We have applied for funding, but to be eligible we need to have 5% of funding in place beforehand. This is where you come in!

Help us reach our 5% target to carry through our plans for the museum by donating through the link on the left. The money is to design and build the museum, staffing, and for our 3-year community engagement plan. Ever penny will go to give back to the community and showcasing our shared heritage.

Because this project is for and by the community, we also invite you to come along the 22nd of May for a behind the scenes meeting on the Maryhill Museum. We’ll talk about our future plans for the museum, share ideas, and you can hear more on how to get involved and help us research our own wee part of Glasgow! Sign up and read more about the event here.

Monday Memories: Going to the Pictures

Monday 28th January

1.30pm - 3pm

Join us for the first of our Monday Memories sessions at Maryhill Burgh Halls. A monthly social group to have a cup of tea and a biscuit and talk about our shared history.

This month we are 'going to the pictures' and have a variety of objects and photographs relating to the heyday of silver screen.

Light refreshments will be served.

Community Museum Day

Saturday 26th January, 2019

11am - 3pm

What does Maryhill mean to you? Become a curator for the day and show us!

Learn how a museum works, help us conserve our collection, have a go at photographing objects or try writing a museum label! Yours could be picked to be part of our first ever community pop up museum right here in Maryhill Burgh Halls!

Why not bring along an object or a photograph that you think sums up a piece of Maryhill history - a matchbox from Bryant and May or a photo of you dolled up to go to the dancin in the 70s? Its all part of our community history and we want to show it off!

You'll also get a chance to see the objects in our collection and have a say in how they are displayed.

This is a drop in event so come along any time. Suitable for ages 5+.

Hands on History - Going to the pictures

Monday 28th January 2019, 11am - 1pm

Do you remember the first film you ever saw in the pictures? Or have memories of the beautiful cinemas that used to exist in Maryhill and across Glasgow? If so, we have a treat for you!

In this session we will look at some original artefacts from the golden age of cinema and you can see some photos of cinemas in their heyday. Bring along your own photos or tickets to jog your memory and share with others. This event will also be the first meeting of the Maryhill History Group so stick around after for a chat and a cup of tea to find out more.

This is a free drop in session, suitable for all ages, so you can come whenever you like!

Welcome to the Maryhill Burgh Halls Blog

Here you will find in-depth research and snippets into our local history which has been conducted by volunteers, staff and friends of the Halls.